Usually, you don’t want to have something looping forever and ever. It serves no purpose. There has to be a condition when whatever needs to be done is finished and the loops stops. Unless we want to write a program to specifically do something it’s not supposed to. Which is precisely what we will do in this post. None of this should work, but it does.

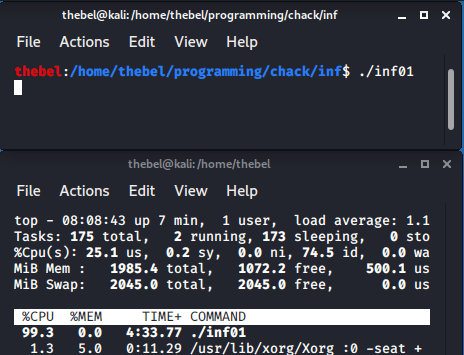

inf01 running.What we are going to do is construct a simple infinite loop to demonstrate how we can manipulate data on the stack. The technique we will use is shown by Prof. Jerry Cain in his lecture series “Programming Paradigms” at Stanford.

The finished product looks like this:

#include <stdlib.h>

void inf();

int main()

{

inf();

return 0;

}

void inf()

{

int foo[1];

foo[3] -= 5;

}

You may not believe that this is an infinite loop, so I will prove it to you! We will see that there is a suprisingly intricate set of mechanics that cause the above program to run forever.

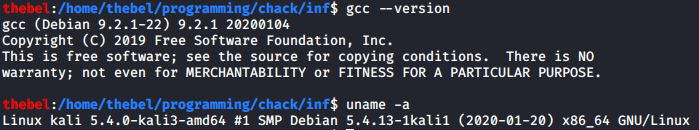

First, the GCC version and OS:

The GCC version is important since the index (foo[3]) may be different depending on the compiler version. For example, using version 4.8.5 at work, the index will be 6 instead of 3.

Let’s fire up GDB and have a look at our program. This is how we will see that it is, in fact, an infinite loop.

hebel:/home/thebel/programming/chack/inf$ gdb

GNU gdb (Debian 8.3.1-1) 8.3.1

Copyright (C) 2019 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

License GPLv3+: GNU GPL version 3 or later <http://gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html>

This is free software: you are free to change and redistribute it.

There is NO WARRANTY, to the extent permitted by law.

Type "show copying" and "show warranty" for details.

This GDB was configured as "x86_64-linux-gnu".

Type "show configuration" for configuration details.

For bug reporting instructions, please see:

<http://www.gnu.org/software/gdb/bugs/>.

Find the GDB manual and other documentation resources online at:

<http://www.gnu.org/software/gdb/documentation/>.

For help, type "help".

Type "apropos word" to search for commands related to "word".

(gdb) file inf01

Reading symbols from inf01...

(gdb) break inf01.c:1

Breakpoint 1 at 0x1129: file inf01.c, line 7.

Breakpoint 1 at 0x1129: file inf01.c, line 7.

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/thebel/programming/chack/inf/inf01

Breakpoint 1, main () at inf01.c:7

7 inf();

(gdb)

We will begin by opening up the binary using the command file inf01. We will also set a breakpoint at line 1 using break inf01.c:1. You can set the breakpoint elsewhere, this is just so we can step through the program, one statement at a time. Finally, we will run the program. It will automatically break at the first statement, which is the call to inf() inside main().

Let’s now step a few times and see where we get:

(gdb) step

inf () at inf01.c:16

16 foo[3] -= 5;

(gdb) step

17 }

(gdb) step

inf () at inf01.c:16

16 foo[3] -= 5;

(gdb) step

17 }

(gdb) step

inf () at inf01.c:16

16 foo[3] -= 5;

The answer is, well, nowhere. We get absolutely nowhere!

Indeed, we can supply a number of steps for step to take, like 100 or 1000, but still, we end up where we started:

(gdb) step 100

inf () at inf01.c:16

16 foo[3] -= 5;

(gdb) step 1000

inf () at inf01.c:16

16 foo[3] -= 5;

(gdb)

To understand why this happens, we have to take a closer look at how inf() is written.

The Return Address

Every time a function is called, something called the return address is stored on the stack. This is the address of the instruction to return to after the function has been called. In our example, main() consists of two statements: the call to inf() and the return statement. After inf() has finished doing its thing and returns, the computer needs to know where to continue from. The return address will therefore point to the instruction right after the call to inf(). Hence, why main() would then return the value 0.

We can verify this by looking at the disassembly of main():

(gdb) disas main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x0000555555555125 <+0>: push rbp

0x0000555555555126 <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x0000555555555129 <+4>: mov eax,0x0

0x000055555555512e <+9>: call 0x55555555513a <inf>

0x0000555555555133 <+14>: mov eax,0x0

0x0000555555555138 <+19>: pop rbp

0x0000555555555139 <+20>: ret

End of assembler dump.

The call to inf() occurs at 0x000055555555512e. The return address for inf() must then be the next instruction, i.e. 0x0000555555555133. Let’s check:

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/thebel/programming/chack/inf/inf01

Breakpoint 1, main () at inf01.c:7

warning: Source file is more recent than executable.

7 inf();

(gdb) step

inf () at inf01.c:16

16 foo[3] -= 5;

(gdb) x/gx $rsp+0x8

0x7fffffffe138: 0x0000555555555133

(gdb) x/i 0x0000555555555133

0x555555555133 <main+14>: mov $0x0,%eax

Here, we’ve stepped into inf() and had a look at a piece of data stored on the stack for that function. That piece of data is located at an offset of 0x8 bytes from the stack pointer $rsp. For more info on how the stack looks, check out Eli Bendersky’s blog post on the subject. Knowing how the stack frame is laid out, we can figure out the offset from $rsp of the return address. As an homage to the gratuitous cruelty of my college professors, this is left as an exercise to the reader.

The piece of data stored at $rsp+0x8 is the return address for inf(). We accessed it here using GDB’s examine command: x/gx. Because the return address is, well, an address, we can inspect it as well. Because we know it’s an instruction, we can tell GDB to interpret it as such using the i option: x/i. Indeed, the instruction at 0x0000555555555133 is none other than the instruction right after the call to inf().

So now that we understand how the return address works, we can try to manipulate it.

Abusing C’s Array Notation

In essence, in order to produce an infinite loop, all we have to do is set the return address for inf() to the call instruction used to call inf() in the first place. That way, whenever inf() finishes up and returns, it just returns to where it was called from. And so it runs again. And returns to the call. And runs again. Ad infinitum.

How do we modify the return address? We are going to use C’s leniency when it comes to array notation and how this can be used to overflow an array variable. Let’s review the code for inf():

void inf()

{

int foo[1];

foo[3] -= 5;

}

The first statement is a declaration of an array of integers of length 1 (int foo[1]). What the compiler will do, is allocate a space the size of an int (4 bytes) on the stack. Doing it this way ensures that the variable foo is not optimized out by GCC.

If foo is an array of length 1, why can we refer to the 3th (that’s not a typo) element in the next statement without the compiler complaining? The reason is how C treats array notation. In fact, array notation is simply syntactic sugar in C. This means it exists as a convenience for the programmer, but actually masks some other underlying behavior. See the top response form this StackOverflow thread for an example of what C’s handling of array notation allows you to do. We will use this horrifying property in a future blog post to create a toy program that prints the Fibonacci sequence in an unnecessarily obfuscated way.

In C, foo[3] is evaluated as *(foo + 3). Now what on earth does that second expression mean?

Let us treat foo as a pointer to the 0th element of the array. In other words, the de-reference of foo, *foo is equivalent to foo[0]. Consequently, the 1th element of foo would then have to be located at the address to the 0th element plus the size of an int. Visually, this looks something like this:

+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+

| 0th | 1th | 2th | ... | nth |

+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+

^ ^ ^

| | |

| | foo + 2

| |

| foo + 1

|

foo

Since *foo == foo[0], then we can also write it as *(foo + 0) == foo[0]. Since this is true and since the 1th element is one int-size away from foo[0], then *(foo + 1) == foo[1] must also be true. And it is. We can verify this using GDB (note that 1 is true in C):

(gdb) f

#0 inf () at inf01.c:16

16 foo[3] -= 5;

(gdb) p *(foo + 0) == foo[0]

$22 = 1

(gdb) p *(foo + 1) == foo[1]

$23 = 1

(gdb) p *(foo + 2) == foo[2]

$24 = 1

For those who are a bit more familiar with C, what the compiler does here behind the scenes is actually something like this: *(foo + 1) == *(int*)((char*)&foo + 1*sizeof(int)). The index is multiplied by the size of one element before being added to the address of the 0th element. This is particularly obvious when looking at the disassembly of array addressing in x86.

A corrollary of C’s handling of array notation is also that array bounds checking isn’t really relevant. Yes, GCC and other compilers may issue a warning when an index is outside of the bounds of an array, but we don’t care about that. All we’re doing is a bit of math to calculate an address and then accessing the data at that address.

So now that we know what C does behind the scenes when we write foo[i] for some index i, we can look at how to use this to overwrite data at an arbitrary location.

Accessing the Return Address

The location of the return address is, for better or for worse, an arbitrary location in memory. In fact, because it’s part of a function’s stack frame, it must be stored somewhere close to that function’s local variables. Remember that for inf(), the return address is located at $rsp+0x8.

All we have to do is figure out at which array index i, foo[i] is equal to the return address.

For that, let’s do a bit of arithmetic. First, we need the location of the return address:

(gdb) p/x $rsp+0x8

$34 = 0x7fffffffe138

Next, we need the address of foo[0]:

(gdb) p/x &foo[0]

$35 = 0x7fffffffe12c

And now we can calculate the difference:

(gdb) p/d 0x7fffffffe138 - 0x7fffffffe12c

$36 = 12

Now we know the distance between the 0th element of foo and the return address. It’s 12 bytes. How many array elements is that? Since we’re talking about integers, that’s 4 bytes per element, and so 12 bytes is 12/4=3array elements. Or, as a GDB command:

(gdb) p/d ((long)($rsp+0x8) - (long)&foo) / sizeof(int)

$27 = 3

Hence, foo[3] must equal the return address. Let’s check:

(gdb) p/x foo[3]

$38 = 0x55555133

(gdb) x/gx $rsp+0x8

0x7fffffffe138: 0x0000555555555133

Wait, that’s not right. Those two numbers are different! (Notice the different number of the digit 5.)

Manipulating Bytes

The reason is that an address on a 64-bit machine is going to be 8 bytes in size, while an integer is only 4 bytes in size. However, even though foo[3] captures a part of the return address, this is good enough. Specifically, foo[3] captures the least significant 4 bytes of the return address. Why is this good enough, though?

In order to achieve our goal of returning to the instruction that calls inf(), we must decrement the return address by the size of the call instruction. Let’s review the disassembly of main():

(gdb) disas main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x0000555555555125 <+0>: push rbp

0x0000555555555126 <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x0000555555555129 <+4>: mov eax,0x0

0x000055555555512e <+9>: call 0x55555555513a <inf>

0x0000555555555133 <+14>: mov eax,0x0

0x0000555555555138 <+19>: pop rbp

0x0000555555555139 <+20>: ret

End of assembler dump.

The return address is 0x0000555555555133, while the call instruction is located at 0x000055555555512e. The difference between the two is 5 bytes. Let’s once again use GDB as our calculator to confirm:

(gdb) p/d 0x0000555555555133 - 0x000055555555512e

$39 = 5

So, all we have to do, is decrement the return address by 5 bytes, so that we return to the call instruction rather than the mov instruction.

Since 5 bytes is a small number, we don’t need to access the entire return address. Rather, it’s enough to access the least significant bytes and decrement those. Let’s say we wanted to decrement the decimal number 10000005 by 5. Let’s assume it is stored int two chunks as 1000 0005. Because 5 is a small number, we only have to access the 0005 portion to decrement it by 5. That’s what we are doing here. If, however, we wanted to decrement that number by 10,000, we would have to access both chunks.

Finally, we decrement foo[3] by 5 in inf() in order to decrement the return address by 5:

void inf()

{

int foo[1];

foo[3] -= 5;

}

Let’s check our work using GDB:

(gdb) step

inf () at inf01.c:16

16 foo[3] -= 5;

(gdb) x/gx &foo[3]

0x7fffffffe138: 0x0000555555555133

(gdb) step

17 }

(gdb) x/gx &foo[3]

0x7fffffffe138: 0x000055555555512e

(gdb) x/i 0x000055555555512e

0x55555555512e <main+9>: call 0x55555555513a <inf>

See how the return address is changed so that it points to the call instruction.

And that, folks, is how you manipulate the return address to produce an infinite loop.

Epilogue

How does foo[3] only accessing the low bytes of the return address work behind the scenes?

To understand this, let’s have a look at how the individual bytes of the return address are actually stored on our machine:

(gdb) x/8bx $rsp+0x8

0x7fffffffe138: 0x33 0x51 0x55 0x55 0x55 0x55 0x00 0x00

Pretty weird, huh? The reason is due to the byte order being dictated by the endianness of the machine. A great explanation of this concept can be found here. For our purposes, all we need to know is that the least significant byte is stored on the left, while the most significant byte is stored on the right. By using integer array foo, we are accessing only the least significant 4 bytes of the return address. Output in a more readable form:

(gdb) x/wx $rsp+0x8

0x7fffffffe138: 0x55555133

Notice that the order is reversed compared to the previous output. If we decrement the above by 5, the entire return address is decremented by 5. In fact, since 5 is less than the maximum number expressed by a single byte (2^8 == 256), it would even be sufficient to access only the lowest byte and decrement that by 5.

Can you come up with a toy program that uses an array of bytes instead of an array of integers? To get you started (sizeof(char) == 1):

void inf()

{

char foo[1];

// ...

}

Try it! What array index do you need to overwrite the return address’ lowest byte?

Hint: try modify the GDB command p/d ((long)($rsp+0x8) - (long)&foo) / sizeof(int) for this purpose.

2 thoughts on “A Simple Infinite Loop”