Zeroing out data in memory costs CPU cycles. It’s often avoided, including in the case of malloc() or the callstack. When a function is called, a stack frame is created to house the return address, the frame pointer, function arguments, and local variables. However, when the function returns, that data is not removed. It stays in memory.

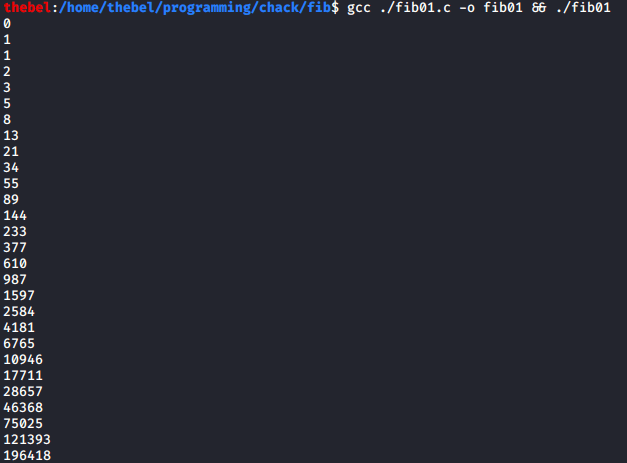

In this post, we will generate the Fibonacci sequence using this mechanic. The program and its output are below:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#define FIB_MAX 200000

void a(int m);

void b();

void c();

void d();

void e();

int main (int argc, char** argv) {

int fib_max = (argc > 1) ? strtol(argv[1], NULL, 10): FIB_MAX;

a(fib_max);

while (1) {

b();

c();

d();

e();

}

}

void a (int m) {

int i = 0;

int j = 1;

int k = m;

}

void b () {

volatile int i, j, k;

printf("%d\n", i);

}

void c () {

volatile int i, j, k;

(j > k) ? exit(0) : (void) 0;

}

void d () {

volatile int i, j, k;

j += i;

}

void e () {

volatile int i, j, k;

i -= j;

i *= -1;

}

Please note that this mechanic is not to be used in production code (obviously). Especially not with such (deliberately) obtuse function names like a() or variables called i even though they aren’t counters. This applies to all of the silly toy programs presented on this blog.

Stack Frames Are Not Zeroed Out

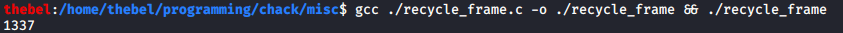

We can verify that stack frames stay put by writing a toy program in C that calls two functions, foo() and bar(). The latter will print the value of the variable a which was initialized inside the former:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

void foo();

void bar();

int main()

{

foo();

bar();

return 0;

}

void foo()

{

int a = 1337;

}

void bar()

{

int a;

printf("%d\n", a);

}

Even though a is not initialized inside bar(), it still prints 1337:

The reason this works is because foo()‘s stack frame will not be zeroed out before bar()‘s stack frame is created. Because of C’s leniency, we can use a variable before initializing it, allowing us to take advantage of the fact that the layout of foo()‘s and bar()‘s stack frames will be the same. The reason they are the same is because both have the same number of arguments (zero) and both declare exactly one variable of the same size (an integer).

Back to Fibonacci

Clearly, one can use the above mechanic to produce some strange behaviors. I’ve always liked the idea of the Fibonacci sequence, because it’s easy to generate and is also somehow elegant. Because it’s so simple, I find it’s also a great candidate for obfuscation. Why obfuscate? Because it’s fun to write toy programs that make people scratch their heads.

Let’s start by looking at our main() function:

int main (int argc, char** argv) {

int fib_max = (argc > 1) ? strtol(argv[1], NULL, 10): FIB_MAX;

a(fib_max);

while (1) {

b();

c();

d();

e();

}

}

fib_max is the maximum element of the Fibonacci sequence we will generate. We will use this later. The call to a() sets up the initial values of the Fibonacci sequence, 0 and 1, as well as the maximum, fib_max.

What’s more interesting is the contents of the while loop. This loop is infinite. But that in itself isn’t interesting. What is, is what the loop achieves: each of the functions b() through e() share the same layout of their stack frames. Similarly to foo() and bar() in the toy program of the previous section. Each of the functions b() through e() sets up three variables:

volatile int i, j, k;

These are marked volatile so that the compiler doesn’t optimize them away since they aren’t all being used in every function. This ensures there are three integer-sized spaces set aside on the stack. In other words, this ensures that nothing overwrites the data inside those spaces. After that, the mechanism is fairly simple: relying on the data in the three variables i, j, and k, we simple calculate the elements of the Fibonacci sequence. In essence:

b()prints the next number,c()decides if we should terminate the loop,d()computes the next element of the sequence,- and

e()computes the element following that (in a slightly obfuscated way).

Don’t Believe Me?

We will prove that the above mechanism works by inspecting our program in GDB. In order to be able to inspect our program in GDB, we will compile it using the following command:

$ gcc -g -O0 ./fib01.c -o fib01

The -g flag ensures that debug information is included in the resulting binary. On the other hand, -O0 disables optimization. Then, we launch GDB, load the binary, set our breakpoint, and run the program:

thebel:/home/thebel/programming/chack/fib$ gdb

GNU gdb (Debian 8.3.1-1) 8.3.1

[...]

(gdb) file fib01

Reading symbols from fib01...

(gdb) break fib01.c:1

Breakpoint 1 at 0x1164: file ./fib01.c, line 14.

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/thebel/programming/chack/fib/fib01

Breakpoint 1, main (argc=1, argv=0x7fffffffe248) at ./fib01.c:14

14 int fib_max = (argc > 1) ? strtol(argv[1], NULL, 10): FIB_MAX;

How Locals Are Stored

The interesting bit for us starts when a() is called and sets up the stack frame. Let’s step into a() and output the addresses at which the variables i, j, and k will be stored:

(gdb) step 2

a (m=200000) at ./fib01.c:29

29 int i = 0;

(gdb) printf "&i=%p &j=%p &k=%p\n", &i, &j, &k

&i=0x7fffffffe12c &j=0x7fffffffe128 &k=0x7fffffffe124

They are stored in “reverse” order, with k coming first and i last. Hence, why k‘s address is the lowest and i‘s is the highest. The reason the variables are stored in this order is because the stack grows from high addresses to low addresses. In other words, it grows downwards. Meaning, that variables will then be allocated space from high to low addresses, i.e. “in reverse”. So, to view the values of i, j, and k, all we need to do is examine the three integer-sized spaces starting with k‘s address, represented as &k:

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 0 1431655077 21845

The values are still uninitialized at this point, so they might as well be junk. By stepping through the statements of a(), we can see how the spaces are filled with their initial values. Note that they will fill up from right to left, as the variables are stored “in reverse”:

(gdb) l 29,29

29 int i = 0;

(gdb) step

30 int j = 1;

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 0 1431655077 0

(gdb) step

31 int k = m;

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 0 1 0

(gdb) step

32 }

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 1 0

The highlighted lines are where we see the initialized values: first i, then j, and finally k.

Stepping Through The Functions

Let’s now step into b() and examine the stack again:

(gdb) step

main (argc=1, argv=0x7fffffffe248) at ./fib01.c:20

20 b();

(gdb) step

b () at ./fib01.c:38

38 printf("%d\n", i);

(gdb) p/d i

$1 = 0

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 1 0

The values are still there! Remember, at this point, a() has returned, so its stack frame has been deallocated (though not removed). We can verify that a() doesn’t have a frame on the stack by printing the call stack using backtrace or bt:

(gdb) bt

#0 b () at ./fib01.c:38

#1 0x00005555555551a5 in main (argc=1, argv=0x7fffffffe248) at ./fib01.c:20

If you still don’t believe me, you can examine the disassembly of b() and verify for yourself that b() doesn’t modify the three variables. Below is the disassembly, though figuring it out is left as an exercise to the reader:

(gdb) disas

Dump of assembler code for function b:

0x00005555555551e3 <+0>: push %rbp

0x00005555555551e4 <+1>: mov %rsp,%rbp

0x00005555555551e7 <+4>: sub $0x10,%rsp

=> 0x00005555555551eb <+8>: mov -0x4(%rbp),%eax

0x00005555555551ee <+11>: mov %eax,%esi

0x00005555555551f0 <+13>: lea 0xe0d(%rip),%rdi # 0x555555556004

0x00005555555551f7 <+20>: mov $0x0,%eax

0x00005555555551fc <+25>: callq 0x555555555030 <printf@plt>

0x0000555555555201 <+30>: nop

0x0000555555555202 <+31>: leaveq

0x0000555555555203 <+32>: retq

End of assembler dump.

Now, stepping through b() isn’t actually that easy, since it contains a call to printf(), which prints the current element of the Fibonacci sequence onto the screen. The implemenation of printf() is not trivial and in fact depends a lot on which compiler you use. No matter, we will overcome this obstacle by creating a second breakpoint, this one inside c():

(gdb) break fib01.c:45

Breakpoint 2 at 0x55555555520c: file ./fib01.c, line 45.

If we then continue, using the continue or cont command, we will end up here:

(gdb) cont

Continuing.

0

Breakpoint 2, c () at ./fib01.c:45

45 (j > k) ? exit(0) : (void) 0;

Note the 0 printed on the line following the string Continuing. This is the first element of the Fibonacci sequence and is, appropriately, printed to screen here.

The c() function is the one that decides whether we have reached our limit, in other words whether j > k. Or, to put it into words, it checks whether the next element in the Fibonacci sequence is greater than the maximum element of the sequence we want to print. This won’t be the case, as we can ascertain by printing out the spaces in memory occupied by our friends i, j, and k:

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 1 0

Look at that! The values are still there. In this iteration of the loop, the next function, d(), will not change the values (since j = 0 + 1 = 1). In fact, let’s make our lives easier and set another breakpoint. This will come in handy when we step through the loop multiple times:

(gdb) break fib01.c:52

Breakpoint 3 at 0x555555555227: file ./fib01.c, line 52.

Continuing to that breakpoint and stepping through the function yields little of interest this time around:

(gdb) cont

Continuing.

Breakpoint 3, d () at ./fib01.c:52

52 j += i;

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 1 0

(gdb) step

53 }

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 1 0

Now, let’s add another breakpoint, this one inside e() and inspect the stack memory:

(gdb) break fib01.c:59

Breakpoint 4 at 0x555555555239: file ./fib01.c, line 59.

(gdb) cont

Continuing.

Breakpoint 4, e () at ./fib01.c:59

59 i -= j;

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 1 0

(gdb) step

60 i *= -1;

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 1 -1

(gdb) step

61 }

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 1 1

We can see how the value of i is modified here to become the second element of the Fibonacci sequence, 1.

Another Iteration

This time, if we continue, we will go back to breakpoint 2, and the current value of i (1) will be printed:

(gdb) cont

Continuing.

1

Breakpoint 2, c () at ./fib01.c:45

45 (j > k) ? exit(0) : (void) 0;

And now the rest of the loop:

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 1 1

(gdb) cont

Continuing.

Breakpoint 3, d () at ./fib01.c:52

52 j += i;

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 1 1

(gdb) step

53 }

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 2 1

(gdb) cont

Continuing.

Breakpoint 4, e () at ./fib01.c:59

59 i -= j;

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 2 1

(gdb) step

60 i *= -1;

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 2 -1

(gdb) step

61 }

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 2 1

At the end, the values of i and j are 1 and 2, respectively. If we continue on through the loop’s iterations, we will see that i and j change their values thus:

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 8 3

[...]

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 8 5

[...]

(gdb) x/3wd &k

0x7fffffffe124: 200000 13 8

I’ve left out the boring bits of me miscounting my breakpoint skips and steps (because apparently basic arithmetic is hard). We can keep going like this until j > k and the loop terminates.

Wrap Up

And that’s it! That’s how we can print the Fibonacci sequence in a silly way by using behavior that shouldn’t work in the first place! Okay, that’s a bit a hyperbole. This is technically undefined behavior (see for example the C11 standard draft). But, given the predictable way in which stack frames are manipulated, we can leverage this mechanism to produce some interesting behavior.

I hope you enjoyed it!