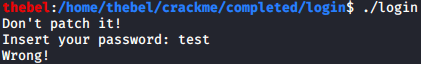

I really enjoyed breaking into the keyg3nme crackme from the previous blog post and so I decided to give another one a go. This one is called login and is available from here. I’ll be working on the binary inside a Linux VM. Let’s run the crackme and see what it wants from us:

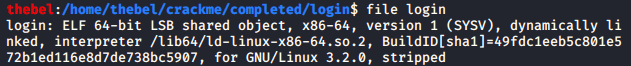

It wants a password. I’m going to assume that this will be some character string, in contrast to the previous crackme, which asked for a numeric key. This time, the binary is also stripped, so we won’t just be able to access the disassembly of main() by referring to it by name:

Consequently, we’re going to have to figure out another way to get to main().

Finding main()

There are several approaches we can use to find main(). One is to run the program inside GDB and stop execution at the input prompt using CTRL+C. We can then output the backtrace at that point and read the address of main() from the first argument to its caller, __libc_start_main(). That looks something like this:

thebel:/home/thebel/crackme/completed/login$ gdb

GNU gdb (Debian 8.3.1-1) 8.3.1

Copyright (C) 2019 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

[...]

(gdb) file login

Reading symbols from login...

(No debugging symbols found in login)

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/thebel/crackme/completed/login/login

Don't patch it!

Insert your password: ^C

Program received signal SIGINT, Interrupt.

0x00007ffff7ee5741 in __GI___libc_read (fd=0, buf=0x5555555596b0, nbytes=1024) at ../sysdeps/unix/sysv/linux/read.c:26

26 ../sysdeps/unix/sysv/linux/read.c: No such file or directory.

(gdb) bt

#0 0x00007ffff7ee5741 in __GI___libc_read (fd=0, buf=0x5555555596b0, nbytes=1024) at ../sysdeps/unix/sysv/linux/read.c:26

#1 0x00007ffff7e78de0 in _IO_new_file_underflow (fp=0x7ffff7fb3a00 <_IO_2_1_stdin_>) at libioP.h:904

#2 0x00007ffff7e79ef2 in __GI__IO_default_uflow (fp=0x7ffff7fb3a00 <_IO_2_1_stdin_>) at libioP.h:904

#3 0x00007ffff7e5550c in __vfscanf_internal (s=<optimized out>, format=<optimized out>, argptr=argptr@entry=0x7fffffffe030, mode_flags=mode_flags@entry=2) at vfscanf-internal.c:263

#4 0x00007ffff7e4fe7e in __isoc99_scanf (format=<optimized out>) at isoc99_scanf.c:30

#5 0x00005555555552f2 in ?? ()

#6 0x00007ffff7e20bbb in __libc_start_main (main=0x5555555552a1, argc=1, argv=0x7fffffffe248, init=<optimized out>, fini=<optimized out>, rtld_fini=<optimized out>, stack_end=0x7fffffffe238) at ../csu/libc-start.c:308

#7 0x00005555555550ba in ?? ()

The address of main() is 0x5555555552a1.

Another approach is to set a breakpoint at the start of __libc_start_main(), since the function belongs to a shared libary and the symbols for it will be loaded once we run the program:

thebel:/home/thebel/crackme/completed/login$ gdb

GNU gdb (Debian 8.3.1-1) 8.3.1

Copyright (C) 2019 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

[...]

(gdb) file login

Reading symbols from login...

(No debugging symbols found in login)

(gdb) b __libc_start_main

Function "__libc_start_main" not defined.

Make breakpoint pending on future shared library load? (y or [n]) y

Breakpoint 1 (__libc_start_main) pending.

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/thebel/crackme/completed/login/login

Breakpoint 1, __libc_start_main (main=0x5555555552a1, argc=1, argv=0x7fffffffe248, init=0x555555555460, fini=0x5555555554c0, rtld_fini=0x7ffff7fe3780 <_dl_fini>, stack_end=0x7fffffffe238) at ../csu/libc-start.c:141

141 ../csu/libc-start.c: No such file or directory.

Yet another approach is possible, by identifying the entry point and finding the call to __libc_start_main(), allowing you to access its arguments. I couldn’t get it to work like in the StackOverflow post because I had to start the program in order to get the correct entry point address. At that point, you might as well use one of the methods above. I’m assuming the reason for having to run the program is because the .text section of the executable is loaded into memory at an offset. Though GDB does normalize memory addresses, it apparently doesn’t bother ensuring the addresses in the process’ .text section are the same as in the binary on disk. Or maybe I’m just too thick to figure it out.

Examining main()

Since the binary is stripped, we can’t just use disas main or expect disas to be able to figure out the boundaries of the main() function. Instead, we will have to do it ourselves. After a bit of playing around with the numbers, I managed to get a clean cut of main() using the x command:

(gdb) x/37i 0x5555555552a1

0x5555555552a1: push rbp

0x5555555552a2: mov rbp,rsp

0x5555555552a5: sub rsp,0x50

0x5555555552a9: mov rax,QWORD PTR fs:0x28

0x5555555552b2: mov QWORD PTR [rbp-0x8],rax

0x5555555552b6: xor eax,eax

0x5555555552b8: mov esi,0x1

0x5555555552bd: lea rdi,[rip+0xd40] # 0x555555556004

0x5555555552c4: call 0x555555555348

0x5555555552c9: mov esi,0x0

0x5555555552ce: lea rdi,[rip+0xd3f] # 0x555555556014

0x5555555552d5: call 0x555555555348

0x5555555552da: lea rax,[rbp-0x50]

0x5555555552de: mov rsi,rax

0x5555555552e1: lea rdi,[rip+0xd43] # 0x55555555602b

0x5555555552e8: mov eax,0x0

0x5555555552ed: call 0x555555555070 <__isoc99_scanf@plt>

0x5555555552f2: lea rax,[rbp-0x50]

0x5555555552f6: lea rsi,[rip+0xd36] # 0x555555556033

0x5555555552fd: mov rdi,rax

0x555555555300: call 0x5555555553e3

0x555555555305: test eax,eax

0x555555555307: jne 0x55555555531c

0x555555555309: mov esi,0x1

0x55555555530e: lea rdi,[rip+0xd2b] # 0x555555556040

0x555555555315: call 0x555555555348

0x55555555531a: jmp 0x55555555532d

0x55555555531c: mov esi,0x1

0x555555555321: lea rdi,[rip+0xd21] # 0x555555556049

0x555555555328: call 0x555555555348

0x55555555532d: mov eax,0x0

0x555555555332: mov rdx,QWORD PTR [rbp-0x8]

0x555555555336: xor rdx,QWORD PTR fs:0x28

0x55555555533f: je 0x555555555346

0x555555555341: call 0x555555555050 <__stack_chk_fail@plt>

0x555555555346: leave

0x555555555347: ret

You can use disas to get the same output once you know the start and end address of a block of code: disas 0x5555555552a1,0x555555555347+0x1. The output is essentially the same. Note the +0x1 at the end. This is a trick to get GDB to print the last instruction. While the ret (“return”) instruction begins at 0x5555555553471, it does not end there. By adding +0x1, you can induce GDB to search for the rest of the instruction and print it out.

Finding Strings

The highlighted lines above represent memory addresses that are computed as an offset from the instruction pointer rip. We can infer from this that these are bits of data in the .data section of the process. Often, these will be string literals found in the code. For example, in the following program, the string "Hello, World!" will be stored in the same way:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main ()

{

printf("Hello, World!");

return 0;

}

Since the strings’ addresses are all in close proximity, they might in fact be stored one after the other. Let’s check:

(gdb) x/6s 0x555555556004

0x555555556004: "Gtu.}'uj{fq!p{$"

0x555555556014: "Lszl{{%\202vx{!whvt|twg?%"

0x55555555602b: "%64[^\n]"

0x555555556033: "fhz4yhx|~g=5"

0x555555556040: "Ftyynjy*"

0x555555556049: "Zwvup("

Indeed they are. Now, the strings don’t look like much but maybe they are encrypted in some way. Notice that a few instructions after each string is loaded, a call is made to a function at 0x555555555348. It’s always that address as well, except in the case of the string 0x55555555602b: "%64[^\n]". That’s probably a scanf() format string.

Perhaps 0x555555555348 is a function that decrypts a string and then prints it. We can verify this theory by setting a breakpoint after each call to this function and seeing whether something is printed to screen:

(gdb) b *0x5555555552c9

Breakpoint 2 at 0x5555555552c9

(gdb) b *0x5555555552da

Breakpoint 3 at 0x5555555552da

(gdb) b *0x5555555552f2

Breakpoint 4 at 0x5555555552f2

(gdb) b *0x55555555531a

Breakpoint 5 at 0x55555555531a

(gdb) b *0x55555555532d

Breakpoint 6 at 0x55555555532d

(gdb) cont

Continuing.

Don't patch it!

Breakpoint 2, 0x00005555555552c9 in ?? ()

(gdb) cont

Continuing.

Breakpoint 3, 0x00005555555552da in ?? ()

(gdb) cont

Continuing.

Insert your password: test

Breakpoint 4, 0x00005555555552f2 in ?? ()

(gdb) cont

Continuing.

Wrong!

Breakpoint 6, 0x000055555555532d in ?? ()

(gdb) cont

Continuing.

[Inferior 1 (process 4637) exited normally]

Turns out, we were right (it helps to have completed the crackme before writing this blog article). Since breakpoint #5 was not triggered, that’s probably where the “success” message is printed. There is definitely a branch before:

0x555555555305: test eax,eax

0x555555555307: jne 0x55555555531c

Reading Input

Now that we’ve figured out where messages get printed in the crackme, we also have to figure out where input is read. Presumably this will occurr somewhere between where the prompt is printed — breakpoint #3 at 0x5555555552da — and the test instruction form above at 0x555555555305. Below the lines between are highlighted for readability:

(gdb) x/37i 0x5555555552a1

0x5555555552a1: push rbp

0x5555555552a2: mov rbp,rsp

0x5555555552a5: sub rsp,0x50

0x5555555552a9: mov rax,QWORD PTR fs:0x28

0x5555555552b2: mov QWORD PTR [rbp-0x8],rax

0x5555555552b6: xor eax,eax

0x5555555552b8: mov esi,0x1

0x5555555552bd: lea rdi,[rip+0xd40] # 0x555555556004

0x5555555552c4: call 0x555555555348

0x5555555552c9: mov esi,0x0

0x5555555552ce: lea rdi,[rip+0xd3f] # 0x555555556014

0x5555555552d5: call 0x555555555348

0x5555555552da: lea rax,[rbp-0x50]

0x5555555552de: mov rsi,rax

0x5555555552e1: lea rdi,[rip+0xd43] # 0x55555555602b

0x5555555552e8: mov eax,0x0

0x5555555552ed: call 0x555555555070 <__isoc99_scanf@plt>

0x5555555552f2: lea rax,[rbp-0x50]

0x5555555552f6: lea rsi,[rip+0xd36] # 0x555555556033

0x5555555552fd: mov rdi,rax

0x555555555300: call 0x5555555553e3

0x555555555305: test eax,eax

0x555555555307: jne 0x55555555531c

0x555555555309: mov esi,0x1

0x55555555530e: lea rdi,[rip+0xd2b] # 0x555555556040

0x555555555315: call 0x555555555348

0x55555555531a: jmp 0x55555555532d

0x55555555531c: mov esi,0x1

0x555555555321: lea rdi,[rip+0xd21] # 0x555555556049

0x555555555328: call 0x555555555348

0x55555555532d: mov eax,0x0

0x555555555332: mov rdx,QWORD PTR [rbp-0x8]

0x555555555336: xor rdx,QWORD PTR fs:0x28

0x55555555533f: je 0x555555555346

0x555555555341: call 0x555555555050 <__stack_chk_fail@plt>

0x555555555346: leave

0x555555555347: ret

There’s a call to scanf() there, which is where our input will be read. Between that and the test instruction, there is something interesting:

0x5555555552f2: lea rax,[rbp-0x50]

0x5555555552f6: lea rsi,[rip+0xd36] # 0x555555556033

0x5555555552fd: mov rdi,rax

0x555555555300: call 0x5555555553e3

First, an address on the stack is being moved into rax. We know it’s from the stack because the address is an offset from rbp. The address, rbp-0x50, had already been used before, at 0x5555555552da:

0x5555555552da: lea rax,[rbp-0x50]

0x5555555552de: mov rsi,rax

0x5555555552e1: lea rdi,[rip+0xd43] # 0x55555555602b

0x5555555552e8: mov eax,0x0

0x5555555552ed: call 0x555555555070 <__isoc99_scanf@plt>

Note that the address was loaded into rax and then rsi. Following that, the string at 0x55555555602b ("%64[^\n]") is loaded into rdi, and eax is zeroed out (it will be used for the return value). Then, scanf() is called. The address in rdi points to a valid scanf() format string, so rsi must be the pointer to the string we are going to input.

Since rbp was not modified, rbp-0x50 still points to the same address at 0x5555555552f2. rbp-0x50 gets loaded into rsi here before 0x5555555553e3 is called. This is not the same function as before. Maybe it’s used to verify the entered password? Seems pretty likely. Especially, since the address of one of our fixed strings is loaded into rdi. Might that be the password? Let’s take a look at that string again:

(gdb) x/s 0x555555556033

0x555555556033: "fhz4yhx|~g=5"

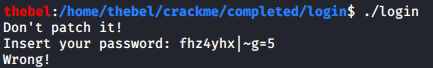

Let’s try to enter that as the password and see what happens:

Clearly, that would have been too easy. So we’re going to have to figure out a way to decrypt the password.

Decrypting The Password

If we assume that all the strings we’ve looked at are encrypted using the same algorithm, then they can also be decrypted using the same function. Specifically, 0x555555555348, which we already know is used to decrypt some of the strings. In order to decrypt the suspected password string, "fhz4yhx|~g=5", all we have to do is step into an instruction that calls 0x555555555348 and replace the address to the string in rdi with the address of "fhz4yhx|~g=5". From earlier, we know that the address is 0x555555556033:

(gdb) x/s 0x555555556033

0x555555556033: "fhz4yhx|~g=5"

Now, all we have to do is set rdi to that address and hey presto!, we should have the password in plain text. Let’s try it:

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/thebel/crackme/completed/login/login

Breakpoint 1, 0x00005555555552a1 in ?? ()

(gdb) x/37i 0x5555555552a1

=> 0x5555555552a1: push rbp

0x5555555552a2: mov rbp,rsp

0x5555555552a5: sub rsp,0x50

0x5555555552a9: mov rax,QWORD PTR fs:0x28

0x5555555552b2: mov QWORD PTR [rbp-0x8],rax

0x5555555552b6: xor eax,eax

0x5555555552b8: mov esi,0x1

0x5555555552bd: lea rdi,[rip+0xd40] # 0x555555556004

0x5555555552c4: call 0x555555555348

[...]

(gdb) stepi 8

0x00005555555552c4 in ?? ()

(gdb) set $rdi = 0x555555556033

(gdb) cont

Continuing.

ccs-passwd44

Breakpoint 2, 0x00005555555552c9 in ?? ()

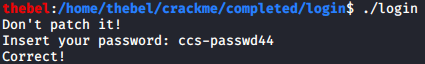

The string "ccs-passwd44" does look suspiciously like it could be a password. Let’s plug it into the crackme:

We got in!

Bottom Line

I’m really starting to enjoy these crackme challenges! Look forward to more of these in the near future. At crackmes.one, there is a huge collection of them of various difficulty levels. If you’d like to learn more about how software works under the hood, give them a go!